Pissing blood

In the third and final installation from Mark and Ellie's 2016 Croatia - Albania cycle, things have taken a troubling turn....

We hadn’t seen a single other touring cyclist until we reached the top of Mount Cika in Llogara National Park and saw the distant dark figures of the Germans slogging up the other side of the mountain towards us.

And what a mountain. The day before, we had surveyed its dark bulk from where we stopped for the night at Orikum, Mark frowning unhappily. The heat was bothering him.

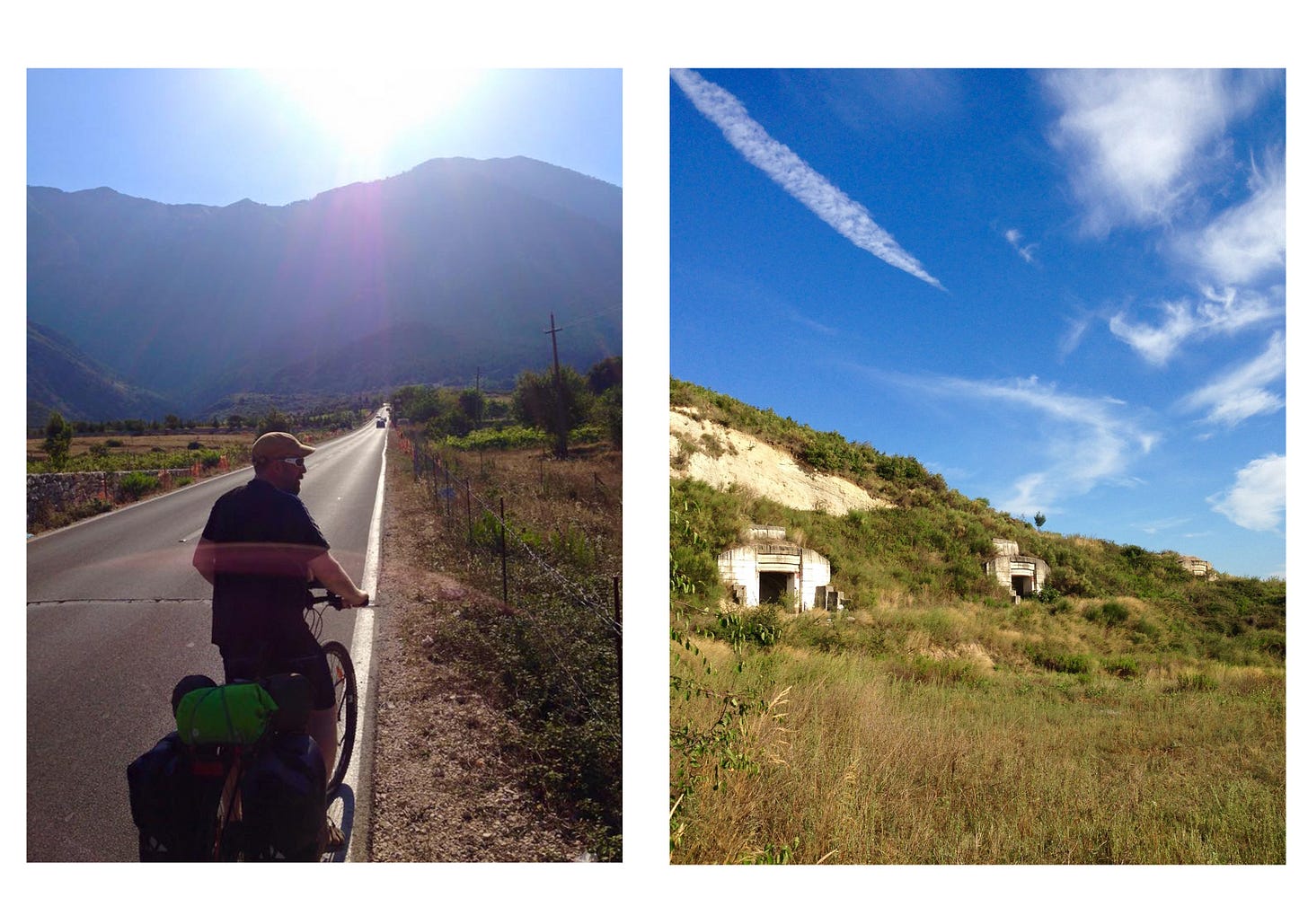

That day we had cycled mostly along a low coast road, past marshy salt flats steaming in the sun and every living thing languishing peacefully, resigned to the sweltering 35°C heat, but waiting for evening. We passed an elderly couple dressed in black, driving a flock of turkeys kicking up dust clouds before them.

Shortly afterwards, we found a bunker that was clearly being lived in, with ragged clothing hanging on a makeshift line near the entrance. We stopped for a break, and a thin figure approached us, a machete-like blade in one hand and a bucket in the other.

In the Albanian countryside, we found English to be rarely spoken amongst the older generation, who were more likely to have Italian. We had no common language to sate this man’s curiosity. His pants were held up with twine.

He gestured at our bikes: yes, we had come a long way. Yes, it was hot. Did he live here, in this bunker? Yes he did. Where were we from? He didn’t understand our answer.

He proffered his bucket, which was full of dusty, bruised black figs. The bucket looked like it had been used to mix cement in a past lifetime, so I guiltily broke my dad’s rule of never turning down hospitality, even though this man clearly did not own much and was offering what he could.

We were picking plenty of wild figs that were more luscious and less dusty than his. We had a little competition going on, vying with each other to see who could pluck a perfectly ripe one from the bike without even slowing down: a free source of energy, growing along all the roadsides much as blackberries do in Ireland. Mark had never eaten fresh figs before.

No, no, we’re ok for figs but thanks for the generosity. We stood together in silence for a few minutes, nodding, squinting around, giving him the opportunity for a good stare at our strangeness. And then we moved on, and he stood looking after us.

All that evening, Mark scowled at the mountain, while I repeated my most irritating catch-phrase: “it´s not as bad as it looks.” The next morning, it was every bit as bad as it looked. From desiccated farmland in the sloping foothills, the climb got progressively steeper until it was a series of viciously tight switchbacks.

It being a weekend, and this being a national park, carloads of families and young couples zoomed past regularly, some winding their windows down to offer yelps of encouragement to us and drop the odd fag packet or drink can while they were at it.

It was beautiful forest, on the shaded side of the mountain. Litter was everywhere: anyone who picnicked here just upped and left it all behind them and there was no sense of shame to littering here. It was natural to finish the last swig of your drink and just casually hurl the bottle into a nearby bush.

We stopped for a rest in a café overlooking a valley that was uncharacteristically shaded and green, almost alpine. We ate an entire box of cookies, eyeing the amount more up we had yet to do. When sugar had propelled us to a bunker near the summit, we stopped for a picture and then a last final kilometre or so to the top, to be rewarded with a dazzling view of the coast, the Adriatic and Ionian seas glittering below us, Greece finally visible.

And below us like ants in their matching black lycra, the Germans, steadily increasing in size until they pulled up alongside us. They were burnished brown, muscular, clad in gear that was expensive even through its dust: wraparound shades, fingerless gel gloves.

We sized each other up and they quickly decided, with the superficial materialism so common to affluent Europeans, that we were some kind of overpacked day trippers. I was wearing a striped cotton shirt from Penneys to keep the sun off my shoulders, a cheap pair of already frayed hiking sandals.

“Where did you come from?” the man asked. “Zadar.” “Zadar? In Croatia?” they said with open disbelief, looking us over once more. How could this pair of unfit, ill-equipped, ungainly clowns have possibly made it from Zadar to here?

We both hate this stuff. The dressage of cycling. The gear, the look. I particularly hate how, in order to be the thing, it seems more important to look the part than be actually doing the thing. The thing that is most liberating about cycling is that, as long as you have a bike of some sort and some food in your belly, it’s absolutely free.

Yet there are all these people who will judge whether or not you are able to rotate the pedals of a bicycle on the basis of how much money you have spent, on the bike, on your gear, and on endless stupid and unnecessary gadgets, none of which turn out to be an improvement on the basic genius of humankind’s best ever invention.

We chatted politely for a bit. They had come from Greece. We were about to take our leave when the woman dropped a parting shot; we encouragingly told them they were near the summit, and had a long pleasant spin to look forward to on the other side. She turned and smirked rather nastily and said, “well if you guys think this was bad, you have a lot more to come today.”

Soon we were speeding down the spectacular mountainside, enjoying kilometre after kilometre of warm breeze and the vistas stretching away from us, free as birds. The fruits of your aching labour in a climb are always rewarded equally in the next glorious descent. Just like in life.

I might have been thinking exactly this, all buzzy with endorphins and sun and love and the beauty of all things, when one of Mark’s rear pannier bags detached itself in front of me and I hit it.

Incredibly, I was moving so quickly that I actually rode over it, but wobbled nastily right after. The adrenaline rush was mighty. I hung back a bit after that and slowed a little for the rest of the descent.

The morning’s climbing started to take its toll on the energy levels in the afternoon when we had reached near sea level again and were buzzing along on the flat.

The German’s words kept ringing in my ears, but there was no sign of another big ascent yet.

Mark had been getting quieter and quieter and more withdrawn on rest stops, until suddenly he came back from a wee behind a tree and said in a chatty, conversational tone, “So, I think I might be pissing blood.”

Worrying about this, and about the German’s words, marred the afternoon a little, even though this was a beautiful stretch of coast. Mark goes quiet when things aren’t good, and I couldn´t get him to give me an accurate assessment of how bad things were. I wanted to know if we should stop, if he thought he needed medical attention. He wouldn’t say he was in pain, only that he felt weak.“But is it bright red, or is it kind of more brown?” I asked. “Is it definitely blood or could it just be that your wee is dark?” At another rest stop, he took a bottle with him and returned and handed it to me, still warm from its time in his innards.

I held it up to the light, and we peered at his piss, and even though it was definitely worryingly pinkish, we had a laughing fit, at ourselves, at the kind of partnership that we were forming. “You really know how to treat a lady,” I told him.

We booked a room in a town for the night. But by the evening, when we started hitting another hill, both of us were fearful that there was a climb equivalent to the one behind us before we reached our destination.

We began toiling upwards towards a small, ramshackle looking village, when Mark suddenly stopped and dismounted and started pushing his bike. “I just don’t think I can go on,” he said. I looked around in desperation.

“We’re going to hitch,” I said. “You can’t do this anymore.”

“We can’t hitch with the bikes. You go on.”

“Don’t be ridiculous. What will you do? We’ll get a lift, there are loads of trucks going past.”

A tantalisingly empty flat-bed trailer roared past as if to illustrate my point. I tried to get Mark to sit on the roadside while I thumbed a ride. The hillside village we were in was a mix of traditional little cottages and ugly, squalid modern apartment blocks. There was not a soul to be seen, but there were cooking smells coming from the flats opposite. A bad time for hitching, when workmen would be hurrying home for dinner, I thought.

He didn’t want to, but eventually Mark sat on a bank of earth while I stuck my thumb out. Almost immediately, a rusting pickup truck screeched to a halt. “Come on, Mark!” I said, thinking we had struck gold. But the driver leaned out his window.

“What you doing? Don’t do this!” He called. “Not safe, not good here. Gypsy town!” He shook his head.

“Well can we have a lift?”

“Where you going?” We told him the name of the town.

“But that’s not far,” he said, and roared off.

We looked at each other. Mark sighed, and heaved himself up, and straddled his bike. “Look, we just have to go on,” he said. “We can’t hitch anyway.” So we set off again, me riding behind him as he laboured slowly up the hill, wobbling slightly. I was seriously worried he was going to keel over.

Coming out of the village, the hill levelled out and we found ourselves on a high, flat road with a dry river valley and farmland to our left, still with no sign of the cursed German’s mountain. We picked up pace; maybe things weren’t so bad. It was cooler now and Mark was going fine.

I heard a distant volley of barks. From a farm below us, I suddenly saw moving shapes haring up towards the road. A pack of dogs was moving towards us with intent. The barking sounded frenzied.

“Mark, you’re going to have to speed up,” I called. The dogs kept coming: yellow eyed and vicious, about to break out onto the road almost alongside us. “Mark, go faster!”

Later, Mark told me he was seeing white stars all over his field of vision as he put on a final desperate spurt. “Fuck off dogs!!” he barked. Mark thinks he can speak dog. Sometimes I don’t think he’s wrong, They definitely know he’s telling them to fuck off, anyway.

As I was behind, I looked back and saw the first dog just metres from me, teeth bared, but we managed to clear them. They gave chase, yelping, but receded into the distance and our pounding hearts continued their journey.

We arrived in our town some 5km later, laughing with relief at how close we had been. The German’s mountains would never materialise, on that day or any of the days to come: Mount Cika would remain the toughest day’s climb of the trip.

Had she said it out of spite, because of our cheerful lack of regard for some hierarchy of cycling we didn’t know or care about, because of our audacity in not conforming to her idea of what a cyclist had to be? Who knew. But one thing I learned was that the biggest obstacles are truly those in the mind. We cycled that day in the shadow of a perceived hardship to come, and that’s what made it hardest.

For two more days, Mark pissed blood. And then he just stopped. What it had been - most likely, I thought, a kidney infection caused by bouts of dehydration – we never really discovered.

Could have been years of buckfast that had built up in his system, and now, in the fresh mountain air, decided to make it's escape!